An Introspective Q&A With Astrophotographer Robert Reeves

December 11, 2017 Figure 1 – Robert Reeves.

Figure 1 – Robert Reeves.Introduction

A renowned amateur astronomer, speaker, author, and astrophotographer, Reeves developed an interest in the night sky at a young age and was propelled into a life-long vocation as a stargazer during the dawn of the space age in the late 1950s and early 1960s. While his expertise includes all forms of astrophotography, he has most recently rekindled his interest in the Moon by embarking on a remarkable program of lunar photography from his home near San Antonio, Texas with relatively modest equipment. In this Q&A with AstronomyConnect.com, Reeves tells of his first experiences as a stargazer and his early efforts as an astrophotographer, and he gives some compelling reasons why we should all become serious students and observers of our nearest celestial neighbor.

Here is our Q&A with Robert Reeves.

Q: Like many amateur astronomers, you were a child of the space age… what are some of your first activities and memories as a stargazer?

A: When I was about 10, the skies in San Antonio were very dark and the Milky Way was easily visible. A fun summer evening activity was to lay on a blanket in the front yard with my mother and watch the stars. At the time I did not know the constellations. In 1957, National Geographic published their big wall map of the stars (it still hangs in my office today) and I began to pick through the major constellations.

In October of 1957, Sputnik was launched and that changed everything. Space became a big deal and dozens of popular publications promoted space exploration. One showed a concept illustration of a space station with a central hub and two modules at the end of long booms. This concept drew my attention to the constellation Orion for the first time: the three belt stars were the station's hub and Betlegueuse and Rigel were outlying modules. (Only later did I learn these stars were part of the constellation Orion). For the Christmas of 1960, I received the Skalnate Pleso star atlas, but I was dismayed to find no lines outlining the constellations. Using the National Geographic map as a guide, I drew in the constellation lines on my atlas. Through that activity, in early 1961, I mastered the constellations.

Q: Since then, of course, you've become something of an expert amateur astronomer. You've written many books about astronomy and astrophotography, and you have a huge amount of experience in deep-sky imaging. But now, you seem to focus mostly on lunar imaging. What is it about the Moon that grabs and holds your interest?

The Moon had my interest from the beginning. The Space Age began just at the time I was old enough to grasp the significance of what was happening and could understand the science and history of it. The Moon was big deal and becoming a destination to be explored. My astrophotography career began with a Moon photo in 1958, and I have continued to photographically explore the Moon, first with a 4-inch reflector and 35mm camera and later after military service with a Celestron-8 and Nikon F camera. When digital photography arrived I also applied it to the Moon and found all my years of film lunar imaging were obsolete. The same thing happened when I started using a ToUcam webcam to image the Moon through the Celestron-8. Once again, all previous work was obsolete. That trend continues today with better cameras and upgraded telescopes.

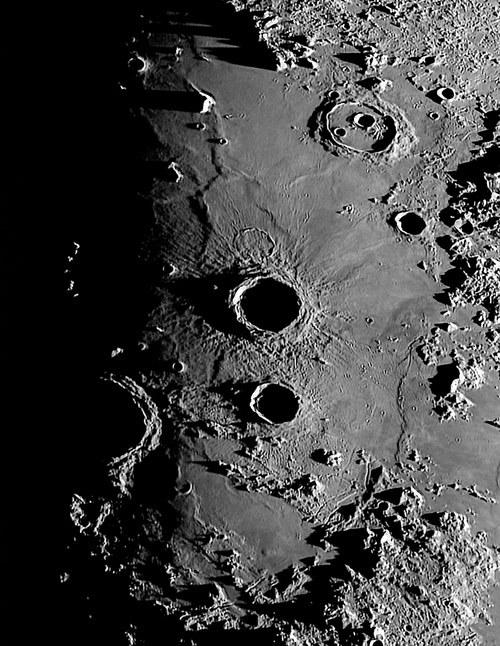

Figure 2 – The crater Archimedes at sunrise. Image courtesy of Robert Reeves.

Figure 2 – The crater Archimedes at sunrise. Image courtesy of Robert Reeves.The beauty of the Moon is that I can image it from home without chasing dark skies. I now live about a mile from where I enjoyed the urban Milky Way in the 1950's, but now I see a half dozen stars on a good night. But the Moon cares not about light pollution, so it gets a greater share of my attention. It keeps my attention because it was once a destination explored by American heroes who rode a pillar of fire and dared to set out for another world. The Moon is a dynamic target, changing night to night, even hour by hour. It is also the only world in space where we can examine its detail and geology at kilometer resolution using a modest telescope. There is much to love about the Moon.

Q: When did you take your first image of the Moon? What was your telescope and camera set-up?

A: My first shot was of Moonrise from my bedroom window. It was taken in 1958 with a WWII era 120-format folding camera that opened up and extended the lens on a bellows. In 1960 I also used that camera to begin star trail pictures and to photograph the passage of the bright Echo 1 balloon satellite launched in late summer of 1960. I also used that camera and a 4-inch reflector to shoot the lunar eclipse of March 1960. By 1962 I was allowed to use the family 35mm camera, a Kodak Retina 2a, to shoot the Moon and begin tracked exposures of constellations on Ektachrome slide film.

Q: What's your current lunar imaging set up? Where do you do most of your observing and imaging these days?

A: Today I use two telescopes on the Moon, a Celestron-11 EdgeHD that I received about four years ago, and a Sky-Watcher 180mm Maksutov-Cassegrain. My lunar camera is a Celestron Skyris 236M. I built a roll-off building observatory on top of my garage in San Antonio. The telescope sits on a Losmandy G11 atop a sand-filled steel pier that passes through the roof and rests on the garage floor. I didn't want to permanently modify the concrete floor, but the pier is so heavy that vibrations rarely bother me. I have used the Sky-Watcher exclusively for two years now because its smaller aperture is more forgiving of the local poor seeing. After two years I feel I have maxed out its capabilities. It is a stunning performer for only 7-inch aperture, but I want better resolution and after the New Year I will reinstall the C-11 and take my chances with the seeing. My goal every time I image the Moon is to improve on what I have already done. To achieve that goal, I have to move back to the larger scope and hope for good seeing.

Q: What kind of resolution of the lunar surface can you get with this set-up?

Resolution is seeing-limited, of course, and with good seeing and a Barlow, I have achieved one-kilometer resolution with both the C-11 and the 180 Mak. That is a good resolution for earth-based imaging, and that threshold is rarely bettered. But I try!

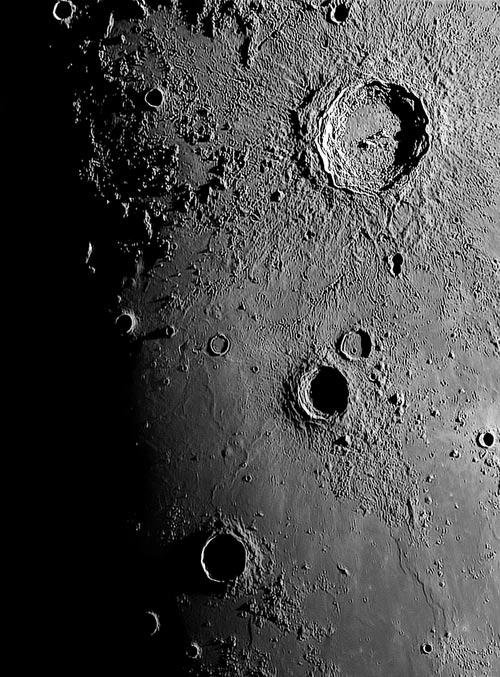

Figure 3 – The craters Copernicus, Reinhold, and Lansberg. Image courtesy of Robert Reeves.

Figure 3 – The craters Copernicus, Reinhold, and Lansberg. Image courtesy of Robert Reeves.Q: Is lunar imaging easier or harder than planetary imaging or deep-sky imaging?

A: Its apples and oranges. Each has its own challenges. Lunar and planetary depend on long focal length and great seeing, deep-sky requires aperture and great tracking and guiding. I have to say, in my opinion, that lunar imaging is easier. I can open the observatory and be imaging the Moon in five minutes. Sometimes it takes me longer than that just to find a planet with the very narrow field of view with a planetary camera. And, of course, I can spend half the night doing a single deep sky image while I can get 20 lunar images within an hour.

Q: For someone who wants to get into lunar imaging, what are your suggestions for a telescope, camera, and software (not brands, necessarily, but specifications)?

A: Affordable refractors traditionally have shorter focal lengths, something not helpful for high lunar detail. An 8- to 11-inch SCT or a Mak would be a best balance between affordability and long focal length. The current crop of planetary cameras is great, so for example, Celestron Skyris, ZWO, QHY, they all work great. For a Barlow lens, which is needed to get a longer focal length, it's important to spend some money and get a premium unit. I use a Seibert Optics 1.5X Barlow and a Televue 2.5X Powermate and recommend both without hesitation. For software, image capture is done with the freeware Firecapture, image stacking is done with the freeware Autostakkert, and image processing is done with Photoshop CC.

Q: How about suggestions for a good 'how-to' book or other educational resources for new lunar imagers?

A: Hmmm... that's a tough question. There are a lot of good books out there, but nothing really recent. My three books, Michael Covington's two books, and a number of older classics from the film era which are still relevant because the basic technique is still similar despite the move from film to silicon sensors. Frankly, I don't know what to recommend as I developed the bulk of my lunar imaging techniques on my own. I will have a new book out as well in the future.

Q: Some experienced observers think the Moon is just a dead and unchanging world that gets in the way of deep-sky observing. How would you persuade them that the Moon is worthy target itself?

A: As mentioned before, the Moon is a dynamic world that changes before our eyes from night to night. It is only a quarter-million miles away and we can see more detail on the Moon with our naked eye than you can on other planets through a telescope. It is a target we can see from a bright urban backyard, no long trip to a dark site required. Once you understand how the Moon was created and how its geology works, the Moon is an amazing playground to explore. And of course, reaching the Moon was once a national goal, and it is the only other world ever visited by humans.

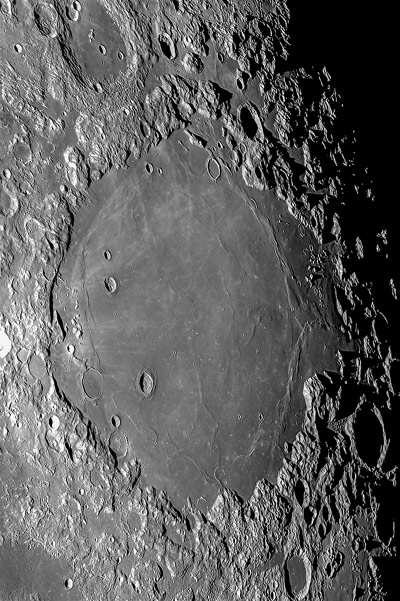

Figure 4 – The craters Langrenus and Petavius. Image courtesy of Robert Reeves.

Figure 4 – The craters Langrenus and Petavius. Image courtesy of Robert Reeves.Q: How about visual observing of the Moon… what's a good choice for telescope, eyepieces, and accessories?

A: I have no specific recommendations. The Moon is a great target in ANY telescope. The limitation is the instrument's quality. A cheap telescope will disappoint, a quality telescope will delight.

Q: For a newcomer to visual lunar observing, what's a good way to get started identifying features and understanding what they're all about? Are there any observing projects you suggest beginners undertake to increase their knowledge and enjoyment of lunar observing?

Understanding how the Moon formed, how its features came into being, and understanding and identifying various geological features is important for a satisfying lunar observing experience. Until my own book on the Moon (no firm publication data yet, but it is at the publisher) the best source for an understanding of the moon for the amateur observer is probably The Modern Moon by Chuck Wood. I think it is still in print, and if not, it is certainly on the used book market. Also, the RASC (Royal Astronomical Society of Canada) has an excellent lunar observing program as does ALPO (Association of Lunar and Planetary Observers) and the Astronomical League.

Q: Are there any opportunities remaining for research or discovery for amateur lunar observers?

A: I believe the days of amateur lunar research are behind us. There is a cadre of diehards that continue to plot lunar domes, conduct mineral surveys with color filters, and things like that. But the hard science is now all spacecraft based. We have scientifically done what we can do from Earth through a telescope. The Moon is now for us to enjoy through the eyepiece.

Q: The Moon is an obvious and popular target for astronomy outreach. Do you have some suggestions to make the Moon more interesting during outreach events, especially for younger observers?

A: Aside from showing the Apollo sites where we have visited, I like to talk about the history of various lunar features, both how our understanding of their nature has evolved over the centuries and how and what they were named after.

Figure 5 – The Mare Crisium ('Sea of Crises'). Image courtesy of Robert Reeves.

Figure 5 – The Mare Crisium ('Sea of Crises'). Image courtesy of Robert Reeves.Q: What are some of your favorite lunar features? What's the best time of the lunar cycle to observe them?

A: Oh my! They are all my favorite. It's like asking a parent which is their favorite child... a good parent can't choose one over the other. Once I did an experiment using the free software Virtual Moon Atlas to view the Moon from different viewing angles that are impossible from Earth. I found that no matter which way I look at the Moon, there was still a stunning diversity of features to fascinate an observer. The key is, of course, to understand what we are looking at on the Moon. Some basic knowledge of how the Moon evolved goes a long way to making a viewing session a delightful experience.

Q: Do you believe that humans will return to the Moon someday? What would such a return look like?

A: A return to the Moon has been a political football thrown by three different U.S. presidents who only wish to deflect attention from their own failing policies. Although I wish with all my might for a human return to the Moon, I do not see it happening in the modern U.S. political climate. The next footprints on the Moon will either be Chinese or by a program funded by private industry. The U.S. government does not have stomach for the risk or the monetary costs to return to the Moon. Nothing will happen until space funding increases dramatically over current budgets and that will not happen with a do-nothing Congress.

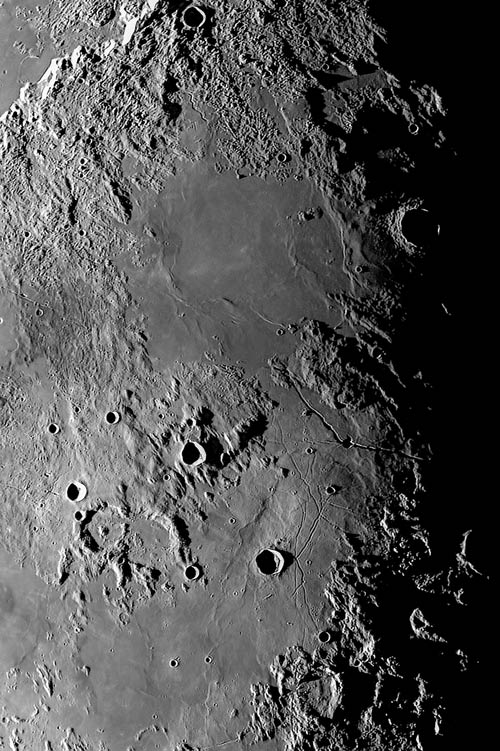

Figure 6 – The region near Mare Vaporum. Image courtesy of Robert Reeves.

Figure 6 – The region near Mare Vaporum. Image courtesy of Robert Reeves.Q: Where can we see more of your lunar imaging work and your books?

A: I post a daily lunar image on 11 different Facebook forums. I write a lunar column in Amateur Astronomy magazine. And Willmann-Bell will soon begin editing and production work on my own Moon book, with a title still not determined. Willmann-Bell take a long time to produce books because of their lengthy vetting process to make them bullet-proof, so I cannot predict a publication date. I also travel to many astronomical conventions and gatherings to talk about the Moon and demonstrate how it is a fascinating backyard target.

Links and References:

Other Resources:

***

This article is © AstronomyConnect 2018. All rights reserved.

Please login or register to watch, comment, or like this article.Rate This Article:

-

Final Announcement: We're Saying Goodbye to AstronomyConnect. Read Our Closing Notice.

Dismiss Notice

New Cookie Policy

On May 24, 2018, we published revised versions of our Terms and Rules and Cookie Policy. Your use of AstronomyConnect.com’s services is subject to these revised terms.